Submitted by Admin on Tue, 16/05/2023 - 16:44

The Mongolia and Inner Asia Studies Unit would like to share this piece written by Unit founder Professor Caroline Humphrey in warm remembrance of Lev Budaevich Radnaev:

LEV BUDAEVICH RADNAEV (1933-2021): AN OBITUARY AND APPRECIATION

CAROLINE HUMPHREY

Anthropologists always have occasion to be grateful to the people who help them in the field – indeed, who often make the fieldwork possible in the first place. I would like to express my gratitude to one such person in the form of an obituary that records his achievements. Lev Budaevich Radnaev was Chairman of the Karl Marx Collective Farm in Barguzin when I conducted research there as a young graduate student in summer 1967. At the time, there was no precedent for such anthropological fieldwork. No western anthropologist had been granted permission for face-to-face field research in Buryatia or indeed in the whole of Siberia. This was still the period of the Cold War, a time of ideological confrontation and mutual suspicion. The risks to Lev Budaevich (and indeed to all of the Soviet people who helped me) in accepting my presence – some young innocent poking their nose into all sorts of matters that locals would normally keep under covers – were not inconsiderable, as my experience in a different collective farm had already shown. Much of my career has been based on my research in Buryatia. This is why I remember and feel gratitude to this day to the people who helped me. Maybe they were instructed to do so, but still it is the kindness and good grace with which I was received that I cannot forget.

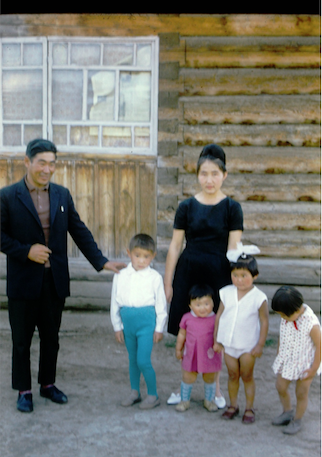

Lev Budaevich was young, in his early 30s, and had only recently been appointed as Chairman when I met him in Bayangol, the central village of the farm (fig 1). He was unassuming and peaceable, with a charming smile. He was of the modern Soviet kind: well-educated as an agricultural specialist in Moscow, quietly self-assured, and dedicated. He gave himself no airs of command; he and his smartly dressed wife and their three children lived in a house that was to my eyes no different from the others that lined the main street of the farm (fig 2). The Radnaevs were native to the area. They belonged to a section of the large Hengelder clan descended from a 19th century ancestor who had ten sons. His descendants were particularly proud of the bravery of their relatives in the Second World War, as Lev Budaevich recalled in an article devoted to the group of kin. Unlike many Soviet officials posted from outside, Lev Budaevich’s start in life was close to that of the other villagers. And he must have loved hunting, because when I arrived he gave me a welcoming dinner in which the main dish was the meat from a deer he had killed that morning. A few days later we had a more formal interview. By then other officials of the kolkhoz had supplied me with information about the farm’s structure, a detailed population breakdown, livestock holdings, infrastructure, agricultural areas, the role and personnel of the Party and local Soviet, as well as maps. I was bursting with information. Lev Budaevich focussed on the history of the farm. He spoke of its origin with five small communes set up in the 1920s, their unification in 1929 into a collective farm called Arbizhil, of its re-naming in 1934 after Sangadin, an early Bolshevik activist, and its second final re-naming in 1937 after Karl Marx. Perhaps this history weighed heavily on his shoulders, for by the time Lev Budaevich took over the farm in 1963 it had massively developed and become a ‘flagship’ enterprise of the Buryat republic (Darmaev 2023).

Arriving in a new place for the first time, one often takes its state for granted without thinking too much about how it got to be that way. In my case, I was to visit the farm a second time in 1975 and then again in the 1990s. Lev Budaevich had been promoted in 1971 to head the Party organisation of the overarching Barguzin District and he stayed in this post until 1982, after which he returned to lead the Karl Marx collective for a further long spell until 1992. My repeated visits allowed me to see that the state of the farm could not be taken for granted – every aspect of it was the result of hard negotiated decisions and investments made under Lev Budaevich’s leadership.

Let me mention a few of these achievements. In 1967, just to travel to the farm was not easy. Roads were not asphalted, and two large rivers had to be crossed laboriously on pontoon rafts that could carry motor vehicles. In 1975 I swept over a concrete bridge that had been built over the river Barguzin and a wooden bridge over the river Ina. Meanwhile, an airfield was also built and daily flights from the district to the capital were organised. In 1967, it did not occur to me to be surprised that the houses in the central farm village had electricity, but I should have been. The region was remote, the distances huge, there were no electricity generating stations anywhere nearby. Most of the scattered herding stations on the sheep pastures still had no power. But during Lev Budaevich’s time as Party Secretary, some of the sprawling state and collective farms of the Barguzin region were split into more manageable smaller units which enabled current to be supplied to almost all of their tiny outlying hamlets. When I first visited people had radios. The most wonderful innovation for the local people during Lev Budaevich’s time was the advent of television. It was a local initiative to establish an ‘Orbit’ television relay system paid for from district sources. It is difficult to comprehend now what a complex and many-sided managerial task it was to be the Chairman of a huge collective farm comprising 142 square miles of land, four villages and a population of 2,300 people, over half of whom were children under 12 years of age. Lev Budaevich oversaw an expansion in production, a rise in wages, and the building of new roads, houses, shops, and a primary school. In the interval between my visits, he engaged constructions teams, including some army units, to build in the central village of Bayangol a hospital complex, a large new middle school, sports and music schools, and a rest home. Lev Buadaevich’s hard work and dedication that went into these achievements was recognised by the award of numerous medals and orders (fig 3).

I have not returned in recent years and do not know how much of this Soviet era rural development still survives. But I know that Lev Radnaev returned to Bayangol in after retirement (fig 4) and that now, two years after he passed away, he is warmly remembered. His widow and children, seen in my photograph from 1967 (fig 1), recently organised a free-style wrestling tournament in Bayangol in celebration of 100 years of his birth and it went very well.